Until pandemic, running was my means to an end. It was a low-cost form of exercise that I could maintain no matter where I was traveling or how much time I had. I’d squeeze in a three-miler before work, between meetings, or on a hotel gym treadmill before bed. I only ever had one goal: cross the run off the list. I didn’t think of running as a notable hobby, let alone leisure or fun. It was what I did before I could “have fun.” I had no formal program around it the way I did with my other hobbies like writing or baking. I wasn’t doing it to impress anyone or myself. It was just my mode of exercise, and I approached it in a healthy way.

When pandemic hit, I was unmoored. In addition to grappling with confusion of the times, I was also devastated by an unexpected breakup. I cried myself to sleep each night, drowning in sorrow. “What is even the point of life right now? What purpose do I have?” I would eventually fall asleep, but not before promising myself I’d wake up to run. Running was my only anchor, and a naive attempt to hide depression and anxiety.

Because I was using it to gloss over my mental state, the role of running in my life quickly transitioned from simple exercise to unhealthy obsession. I went from running twenty miles per week pre-pandemic to running over forty miles per week post-lockdown. I especially looked forward to maxing out my energy on long-run-Saturday so I’d be too tired to think about my emotions and could guiltlessly eat my feelings.

Who says you can’t run away from your problems?

For the next twenty months of pandemic, I woke up each morning to run, and to let my mind ruin my runs. I was running a lot—too much—for all the wrong reasons, and with no meaningful purpose. Good running looks like positive self-talk, hydrating and refueling during and post-runs, and easy effort with natural pace improvements. My running did not look like this. I never felt more alone than while running through a masked, locked down city. Every run was an opportunity for a new mental spiral.

During these runs, I mostly obsessed over personal and professional shortcomings. I relived sad memories. I started too fast so I could hit an impressive pace and post it on social media. I never hydrated or fueled while I ran. I couldn’t fathom taking in calories when I thought I should be losing them. As a result, I often stopped short—too tired or too sad to go on. Despite all the running, I was neither physically nor mentally more fit.

Then, in November 2021, I ran my first race since the world and my world had come crashing down. Waiting at the starting line with thousands of other runners, I actually felt the electricity. Energy from fellow runners is contagious. Between them and cheerers with witty signs, this run was anything but lonely. I was inspired by those around me to run the right way. For the first time in years, this sport (and life) was not so solo. I felt like I was part of something bigger. I stayed in the moment, not running to escape or to prove anything, but to simply run for me, alongside these other people who had chosen to do the same.

I ran the whole time and dance-ran through the finish line.

The same weekend of this half, USWNT-star Abby Wambach ran the New York City marathon—her first. On their podcast, she and her wife Glennon Doyle discussed their respective experiences as runners and cheerers. Abby joked that she was never taking off her medal, because she was officially a champion. Her recounting of the race was perfect.

I think that those first 24 miles, I feel like I truly experienced the entirety of the human experience, every emotion possible. And then, I decided, “Okay, love is going to be the thing that gets me through this.” And then […] like after thinking about it, I think, that actually all of those emotions are love. I think that’s what it is.

My wheels started turning. The half marathon was fun, but I wanted a new running challenge. The natural next step was to run a marathon. But when I considered it, I wondered what other people would think about me. Would they think I was obsessive? An over-achiever? That I am entitled with time because I’m not a manager at work or a parent at home? I also had some doubts of my own. Was it bad to spend so much time on something that wouldn’t get me ahead in my professional life? Would I ruin my mind and body trying to do this?

Hobbyists are criticized for being privileged people who are able to take time away from work for the luxury of leisure. As author Anne Helen Petersen writes in this piece on hobbies, “They have to formalize and extremetize leisure in order to rationalize seeking it.” In considering the marathon, I feared judgment for being one of those people. I felt guilty for my privilege.

Later in the podcast episode, Abby and Glennon are joined by Olympic medalist Shalane Flanagan, who ran six marathons in six weeks. When Glennon asks her why she did it, she responds:

The short answer of everything is because I can. We don’t have to justify our goals all the time to everyone, but because I can, like I have the ability and I love it.

This response obliterated my self-defeating thoughts. The desire to run a marathon coursed through my feet, through my veins, through my synapses. I knew I could do it. “I am going to run a marathon. I’m going to because I want to,” I thought, almost as a practice response for anyone who asked why (throughout my entire training journey, zero people ever asked why).

I promised myself I would do the marathon the right way, for the right reasons, and with the right support network. After many months of unhealthy running, this extreme goal was my healthiest one.

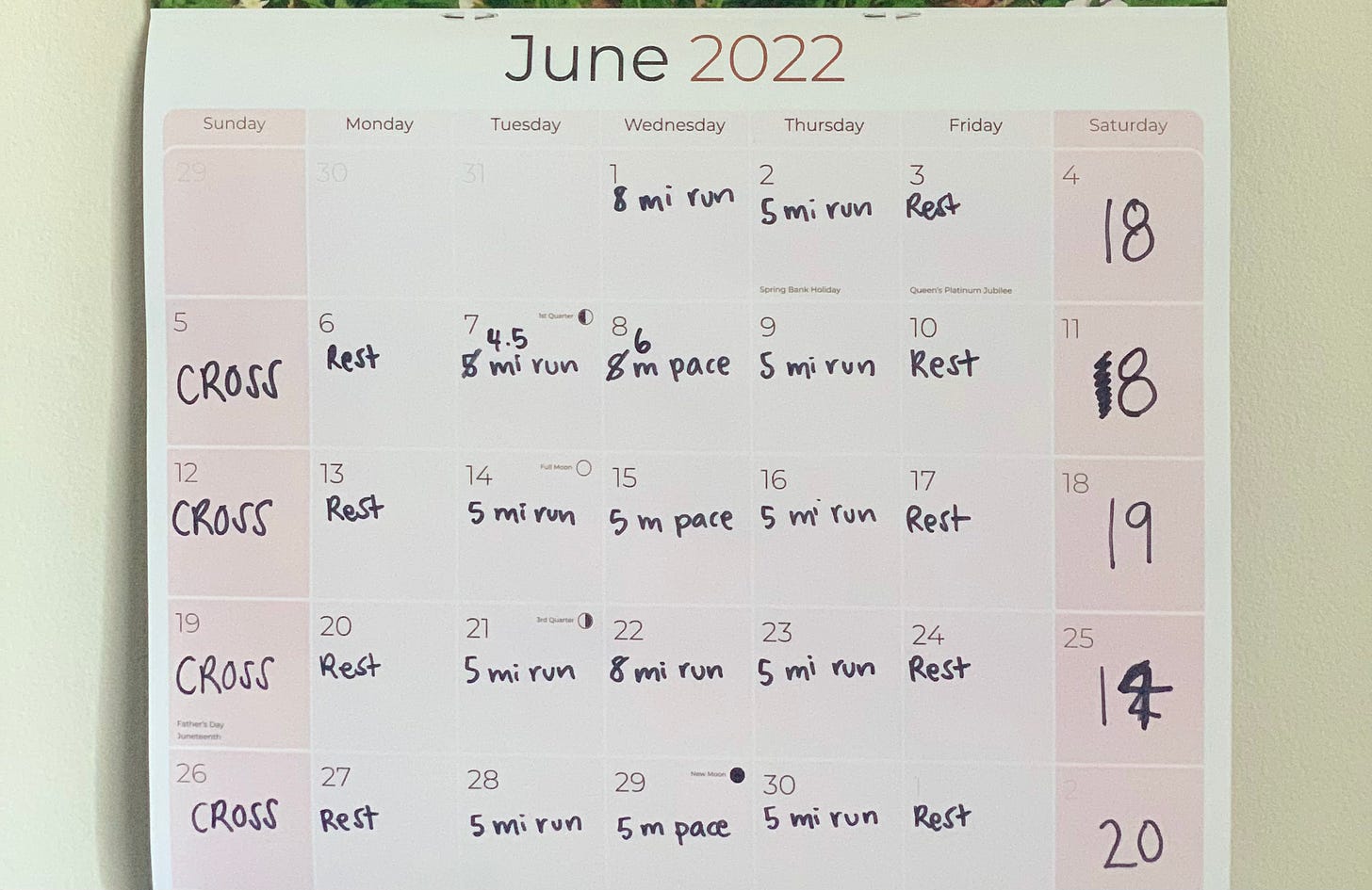

Immediately, I started thinking of myself as a marathoner. I borrowed running cookbooks from the library; I found a training plan online; I bought a wall calendar to visualize my goal. Three months later, I started training.

Now, I was eating fuel not feelings. With each training run, I was running toward a chosen reality, rather than away from one I’d been given. Through Nike’s running app and my own running coach, I learned to celebrate myself and the run while it was happening. To practice positivity while things were going well. To embrace and acknowledge that a “good run” is a feeling, not a pace or a distance. Running became fun because I was running the right way, and reaping the reward. I looked forward to training.

A marathon is objectively “extreme,” but I was running less during the training cycle, looking stronger and more fit, and feeling more joy and mental strength than before. Training was less about running, and more about building mental strength. Call it coincidence, but I didn’t have a single mental health breakdown during my eighteen weeks of marathon training.

At the end of July, I ran my first marathon. I made a note of every moment while running, and spent the next day writing about every mile in my journal. While in many ways, it was “just another run,” it was also an incredible physical and mental accomplishment.

The day after the race, I told my therapist that the marathon had allowed me to reclaim running. “It feels so dumb to say, but it’s mine again. I’m not chasing or running away from anything. I’m not trying to prove anything to others or myself. I’m just, running because it feels good. And I want to.”

“That, is not dumb.” In the minutes that followed, we sat together in silence, acknowledging all that was being said by it.

I took a week off from running after the marathon, then created a new training plan for myself, this time with the goal to take it slow, recover my body, and strengthen my base running. I’m committed to enjoying running the right way going forward.

Hobbies, especially among millennials, tend to be associated with over-exertion and burnout as we each try to side-hustle our way to early retirement or at least some semblance of stability. We continually need to do more and prove something doing it. In her book Can’t Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation, Anne Helen Petersen writes,

“You are what you eat, read, watch, and wear, but it doesn’t end there. You’re also the gym you belong to, the filters you use to post vacation photos, where you go on that vacation. It’s not enough to listen to NPR, read the latest nonfiction National Book Award winner, or run a half marathon.”

I often wonder and worry whether I’m an at-risk product of this generation.

Whether or not I am, I value personal growth through hobbies as much as I prioritize progress in my job. To date, I link all my proudest adult accomplishments with my hobbies. I’ve self-published a book; I’ve founded a little bread business; I’ve run a marathon. Each of these extreme leisure endeavors was borne out of my desire to combat burnout in another aspect of my work or life, and never contributed to it. Formalizing leisure gives me a sense of structure, ownership, and self-worth that I not only struggle to find at work, but that I also don’t want to be attached to my work.

My running journey—from exercise to obsession to formalized leisure—demonstrates that extreme hobbying is not a problem on its own. It only becomes a problem if it is driven by unhealthy motives. Running four days a week to exhaust your mind and body, while on a low-carb diet, is extreme and unhealthy. Running four days a week with a set training schedule, well-rounded meals, and the goal to run a marathon is extreme and healthy.

Identify the activity that energizes you, whether that’s running or gardening or cooking. It doesn’t matter if it’s “instagrammable” or not. It doesn’t matter whether you want to formalize it or not. All that matters is that you choose it for the right reasons—for you. It must fill your cup before it fills anyone else’s.

Explore a hobby because you want to and you can. Set goals around it because you want to and you can. Spend as much time and money on it as you want to and you can. Quit because you want to and you can.

Occasionally, come up for air and ask yourself, “Am I running toward something or away from something?” If the answer is “toward something,” just keep going. Go as far as your heart desires, mind allows, and legs will take you.

Have you been thinking about this too? Do you have a similar (or different) perspective? Start a conversation with Ro and the Unabridged Ro community or share this letter with a friend.

I want to learn more about Unabridged Ro readers (that’s you!) to help guide me in my writing. Please consider sharing your thoughts in this four-minute anonymous survey.

Loved this part— “Formalizing leisure gives me a sense of structure, ownership, and self-worth that I not only struggle to find at work, but that I also don’t want to be attached to my work.”

From a fellow extreme hobbyist who struggles with knowing if “formalizing” is part of a need for external validation or achievement or just a kind way to gift myself motivation and make it easier to keep going :)